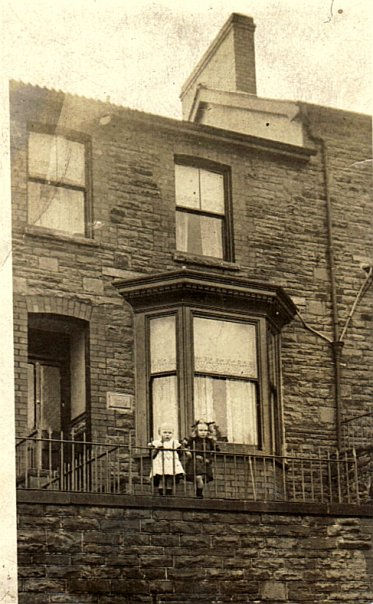

No.23 - A House on Llyn Crescent

- bluecity86

- Jul 21, 2025

- 6 min read

When a house becomes a home, it becomes something greater than bricks and mortar. Estate agents often use the word 'space' - and that is all a house is, a space that needs filling with love and anger, laughter and drama, comfort and mistakes, the smell of cooking and the sound of music.

Despite my suffering badly from car sickness, I loved visiting my Auntie Eva’s home in the Rhondda Valleys. From 1957 she lived there alone, but it always felt a happy and welcoming place, as though the benign spirit of those that had once filled it with life warmed it still. The Rhondda villages were a strange linear kind of urban, the streets ran like dark veins through the countryside, with pit head winding gear and peaked slag heaps dominating the landscape. Those black peaks would loom more sinister after the Aberfan disaster of October 1966.

Hugh

My grandfather, Hugh Thomas Hughes was born in Bangor in 1869 and he became a stone mason like his father. By the time he turned 21, he had moved down to a booming South Wales. He worked on the construction of Barry Docks, staying in Cadoxton, where he contracted typhoid. That could easily have nipped our family tree in the bud, but fortunately for us all, he recovered. When he first arrived in Ferndale, it was a small coal mining village consisting of a single street of timber houses, but collieries were opening all over the region and this rapid expansion required many new, more permanent miners’ cottages.

Eliza

At the Bethel Wesleyan chapel one Sunday he met Eliza Davies, and confidently promised himself, “I’m going to marry that girl.” She worked for a bookseller and almost overnight, Hugh became a great reader. Even though he was Welsh and Wesleyan, with sound prospects, Eliza’s parents were unfriendly towards him. She was easily her father’s favourite of his six children, and he wouldn’t let her entertain a man from North Wales! He didn't know how single-minded his 19 year old daughter could be.

One summer afternoon in 1893 she left her home to go on a Sunday School outing to Barry Island. In those days, such trips were the only opportunity for many to get away from home for a few hours. But this time, Eliza did not go to Barry. With two friends to bear witness, she went to Pontypridd Registry Office, where she and Hugh were married. Afterwards the four went up the mountain to share a bottle of sherry beside 'The Rocking Stone’, a huge boulder that would rock at the touch of a fingertip. Afterwards, they returned to Ferndale as though they had actually spent the day in Barry, and went their separate ways.

Eliza hadn’t the heart to tell her parents, so for two weeks the marriage was nothing more than a folded document concealed in a dusty trunk. Her parents were paying for her to be trained as a seamstress, and to get good value from the lessons, she was meant to pass on all she learnt to her sister Annie. But Annie sensed from Eliza’s demeanour that something had changed. She rifled through her sister’s belongings, and found the marriage certificate. She presented it to their mother, who’s response was, “How on earth are we going to tell your father?”

Although it hadn’t been her intention, Annie had done the couple a favour by letting the cat out of the bag, because Mr Davies was presented with a fait accomplis, and there was little he could do about it, other than scowl.

Building a Home

The newlyweds set up home in a humble basement in Dyffryn Street. Eliza was a smart, proud woman who made her own clothes and insisted on dressing properly before leaving the house. Many of her new neighbours were in the habit of wearing their husbands’ caps and throwing shawls over their shoulders to step out, and some spitefully referred to her as ‘Lady Victoria Buildings,’ thinking her a snob. Her sewing skills had turned their cellar into ‘a little palace,’ impressing the landlord so much that he wanted her to move into another of his properties, so that she could transform that in the same way.

In 1895 they had their first child, Margaret Catherine, but the last five years of the century brought a succession of tragedies. By 1901, she had given birth to seven daughters, with only the first surviving. In 1902, just as she had begun to despair, she gave birth to a healthy boy, William Owen, who would live not for days, or weeks or months, but for the best part of a century. Another six children followed over the next 18 years. Annie May and Eva Maud, Richard David, Hugh Rowland, Olive Doreen (my mother) and finally in 1920, John Colwyn.

Hugh became a foreman for ‘Morris the builders’ and one of their projects was to construct a crescent of houses commanding a spectacular view over Ferndale’s Darran Park. By 1909 the thirteen houses of Llyn Crescent had been completed, and Hugh and his family moved into Number 2. It differed from the other twelve, having an extra bedroom and some ornamental floor tiles. They named it Colwyn House, to acknowledge Hugh's North Wales roots, but it became known to all the family, with great affection, as ‘2 Llyn’.

Hugh continued his work as a building foreman and his ability was highly respected. He was offered a partnership in Australia, by someone who was keen enough to finance the move in order to secure his expertise. At the same time he was offered a job as a foreman on Rhondda Urban District Council, and rather than uproot his family, he accepted that instead.

A fire at an oil store inspired Hugh and a few others to establish a voluntary fire service, and by 1917 he had become Captain of the Ferndale Fire Brigade. He was awarded the King’s Coronation Medal for his work with the brigade in 1937, and even once won a gold medal in a competition for one-handed hose-laying. Because he was in the fire brigade, 2 Llyn had one of the first telephones in the Valleys – the number was Ferndale 4.

My mother recalled her busy family home with great affection. It may have had four bedrooms, but they had to accommodate her mother and father, their eight children and often one or two lodgers besides. The comings and goings gave it the flavour of a benign railway station café and the two great brass-handled iron kettles on the range were always on the boil. Because of different jobs and schools, meals were staggered with Hugh’s lunch being served very shortly after Hughie’s breakfast. Mum said “I had no time to do anything - just lay the table and clear up! For years nobody saw it without food or dishes on it.” Everyone in the busy household had chores, one of Mum’s was cutting squares of newspaper for use in the cold, slug-infested outside toilet.

All Good Things

Both my maternal grandparents died before I was born, so I know them only through the reminiscences of my mother and aunts. In 1950 while trying to climb into the attic at 2 Llyn, Hugh fell off the ladder and he died later in hospital, aged 80. In 1957, Eliza followed him aged 83, and she was buried beside him in Ferndale cemetery. The rest of the large family having dispersed or died, Eva lived alone in 2 Llyn for the next twelve years, but whenever we visited, I felt it remained a happy house.

She eventually had to sell it to join her sister in Pwllheli, at the other end of Wales. 2 Llyn had been in the family since it was built, so she took the trouble to make sure that their cherished home went to someone she felt was worthy of it. A young couple just starting out seemed to fit the bill, and she made the transaction as smooth for them as she could. She often expressed satisfaction with her choice.

I originally posted this story on a Facebook social history group, where it drew many responses, including messages from residents and former residents of Llyn Crescent, which seemed to bear out that there was something special about the street. The comment I found most touching was:

"My name is Hugh Morris and my wife and I bought 2 Llyn from Eva in 1970. We paid her £1,725 (with a mortgage) and when we moved into our house she sent us a cheque for £25 - a considerable sum at that time. We were so grateful to her for her kindness. We lived in 2 Llyn for 28 very wonderful years until 1998. It was where we raised our 2 sons and enjoyed being part of a very special Llyn Crescent community. Your family history has brought tears to our eyes and brought back many of our own happy memories of our time there. Many thanks, Wendy and Hugh."

Comments